Graham Burnett explains how abundant forest gardens and food forests can be grown in any space. Whether it’s a balcony, urban garden or allotment, it’s all down to the planning…

Despite the name, which perhaps implies that they require large amounts of space, forest gardens can be a way of incorporating edible and useful trees and bushes into our home gardens, even in an urban situation. Indeed even those with no gardens at all can adapt the basic principles of forest gardening – I have seen them on allotments and in communal open spaces on inner city housing estates, school playgrounds, and even mini-forest gardens planted in containers and tubs on tower block balconies!

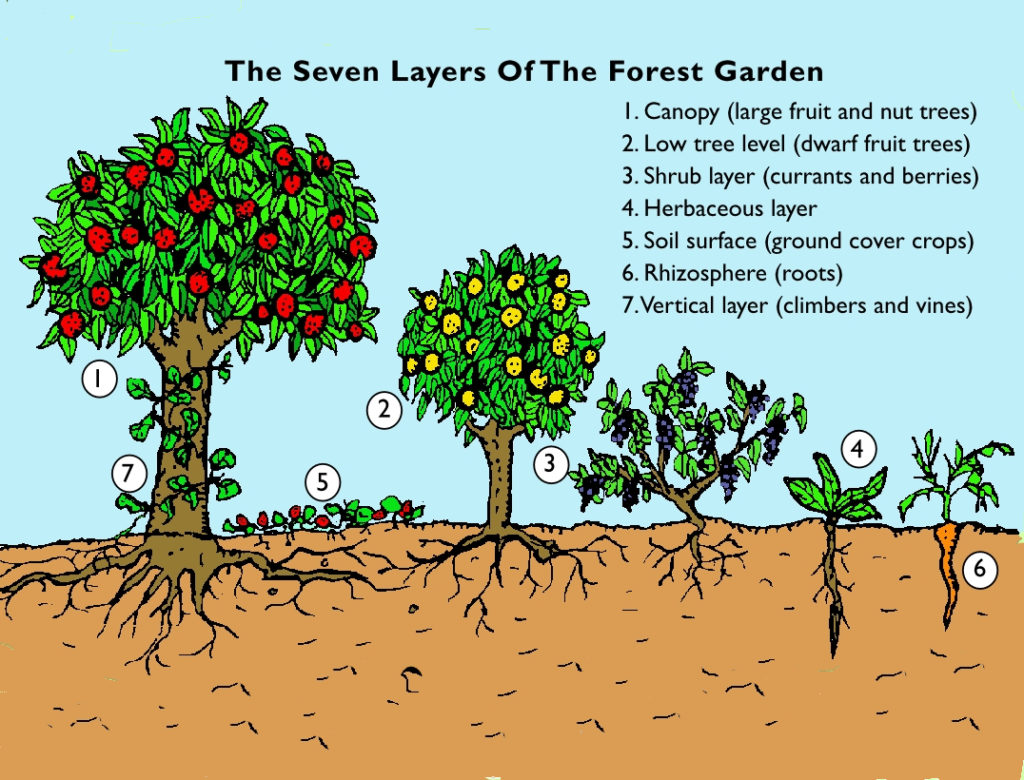

The forest gardening concept was pioneered in the UK during the 1970s by Robert Hart, who examined the interactions and relationships that take place between plants in natural systems. In particular he looked at deciduous woodland, the climax eco-system of a cool temperate region such as the British Isles, as well as the abundant food producing ‘home gardens’ of Kerala in southern India. He observed that unlike many cultivated gardens, nature does not neatly compartmentalise her landscapes with ornamentals growing in one place, vegetables in another and trees in yet a third location. In the woodland several plants such as standard and half standard sized trees, shrubs, climbers and ground cover occupy the same area of space, each ‘stacked’ to find its own requirements within its particular ‘level’ in the system. Replicating the layers of the wild plants of the woodland on a miniature scale with fruits, herbs, vegetables and other plants that are useful to people kind, Robert developed an existing small orchard of apples and pears into an edible landscape consisting of seven dimensions:

1) A ‘canopy’ layer consisting of the original mature fruit trees

2) A ‘low-tree’ layer of smaller nut and fruit trees on dwarfing rootstocks

3) A ‘shrub layer’ of fruit bushes such as currants and berries

4) A ‘herbaceous layer’ of perennial vegetables and herbs

5) A ‘ground cover’ layer of edible plants that spread horizontally

6) A ‘rhizosphere’ or ‘underground’ dimension of plants grown for their roots and tubers as well as subterranean fungi that yield via their fruiting bodies and move nutrients between plants via mycorrhizal associations

7) A vertical ‘layer’ of vines and climbers

Reflecting on the success and productivity of the low maintenance, self-fertilising system that he had created, Robert wrote that:

“Forest gardening offers the potential for all gardeners to grow an important element of their health-creating food; it combines positive gardening and positive health… The wealth, abundance and diversity of the forest garden provides for all human needs – physical needs through foods, materials and exercise, as well as medicines and spiritual needs through beauty and the connection with the whole.”

I had the good fortune to visit Robert’s place in Shropshire a few years before his death in 2000. Stepping into the forest garden felt like entering another world. All around was lushness and abundance, a sharp contrast to the dust bowl aridity of the surrounding prairie farmed fields and farmlands. At first the sheer profusion of growth was bewildering, like entering a wild wood. We’re not used to productive landscapes appearing so disorderly. But it didn’t take long for the true harmony of nature’s systems to reveal themselves, and for the realisation to dawn that in fact it is the Agribiz monocultures, with their heavy machinery, genetic manipulation, erosion, high water inputs, pesticides and fertilisers which are in a total state of maintained chaos. Whereas hectares of land may produce bushel after bushel of but one crop, genetically degraded and totally vulnerable to ever more virulent strains of pest and disease without the dubious protection of massive chemical inputs, a garden of just 0.1 hectares (one eighth of an acre) such as Robert’s can output a tremendous variety of yields.

Inspired by the example of Robert, and more recently the work of Martin Crawford of the Agroforestry Research Trust and others who have learned lessons from both Robert’s successes as well as those things that did not work so well, forest gardening has now become an international movement. Literally thousands have been created in community spaces, private gardens and school grounds both in the UK and around the world:

“Obviously, few of us are in a position to restore the forests. But tens of millions of us have gardens, or access to open spaces such as industrial wastelands, where trees can be planted and if full advantage can be taken of the potentialities that are available even in heavily built up areas, new ‘city forests’ can arise…” (Robert A. de J. Hart)

Creating A Forest Garden – the Process of Design

Having an understanding of a few basic ecological and design principles enables us to work through the process of combining fruit trees and bushes and other (mainly) perennial species in order to create our own highly productive edible landscapes…

Aims and Objectives – What Do You Want?

What are the desired goals and outcomes from your forest garden project? Deciding these at the outset will be very helpful in working out what to plant and the kind of management regime you might decide to adopt. Some possible outputs and products might include:

Edible yields, including fruit (apples, cherries, currants, gooseberries, grapes, medlars, pears, plums, raspberries, etc.), vegetables (Good King Henry, hops, horseradish, Jerusalem artichokes, perennial onions, Turkish rocket, etc.), herbs and salads (lemon balm, lovage, mints, ramsons, sorrel, young tree leaves such as lime, etc.), nuts and seeds ( almonds, hazels, sweet chestnut, etc.), mushrooms and fungi (lion’s mane, oyster, shitake, etc.), beverages (birch sap wine, cider, elderflower cordial, nettle beer, etc.).

Non-edible yields, including medicinal plants (balms, eucalyptus, periwinkle, St Johns Wort, woundwort, etc.), fibres (nettles, New Zealand flax, etc.), craft and basketry materials, poles and canes (bamboo, coppiced hazel, willow charcoal, etc.), building materials, firewood and so on.

Other ‘yields’ from your forest garden might include; educational project, income stream/livelihood, research data, wildlife habitat, venue for parties and celebrations, relaxation space, aesthetic and spiritual yields, the list is endless…

What Have You Got?

Map the existing site and collect information. Finding out as much as possible about your site will give you a clear picture of its limitations and potential resources before you start to think about what will and will not work. Whether your site is shady or sheltered, has a northerly or southerly aspect, is prone to frosts or flooding, the prevailing winds, degree of slope, type of soil and so on will have a major bearing on what trees and shrubs will be suitable or likely to thrive.

Designing The Boundaries

If starting from scratch on exposed land (for example an area of pasture or open field that was previously used for cereal growing), your first priority will be to establish some form of shelter from wind and frosts. Creating a hedgerow shelterbelt of hardy trees and shrubs around your site will provide protection for higher value specimens such as fruit or nut trees whose blossom may be susceptible to damage by late frosts and cold winds that can seriously effect yields. The height of the hedge should be at least one eighth of the size of the area to be protected and needs to be dense in composition in order to provide full protection. Hedging trees and shrubs should be planted at least a year or so before more delicate species go in in order to allow time to get established. Choose multifunctional species that provide wildlife benefits, edible crops or other yields, e.g. crab apple, field maple, hawthorn, hazel, Rosa rugosa, as well as nitrogen fixers such as alder, broom, elaeagnus, etc.

Potential Resources and Obtaining Stock

Research species that fulfil your criteria (i.e. will do well and are suitable and appropriate to your site conditions, including nitrogen fixers and less usual specimens). Create a ‘wish list’ of plants, although this may well need to be edited down! Investigate potential suppliers – support independent and specialist local nurseries where possible. However, buying plants can be expensive so think about other ways you might be able to beg, steal or borrow stock – where could you obtain seeds, cuttings, grafts or other plants cheaply or for free? Avoid false economy however; sometimes ‘bargains’ that end up being sold off cheaply by commercial garden centres or ‘budget stores’ can be of poor quality. Draw up a time scale for the implementation of your project; this will usually be over a period of a few years rather than trying to achieve all of your aims at once.

Designing The Canopy/Layout of Larger Trees

Top fruit (e.g. apples, pears, gages and plums) and nut ‘canopy’ trees will form the backbone of your forest garden, and are the single most important part of the design. These will determine the positioning of all other elements; therefore particular care should be given when considering their location. Most fruit trees are grafted onto rootstocks that will control their height and cropping potential. Take into account the tree’s predicted mature size, including canopy spread – it can be hard to visualise just how much space an apple tree grafted onto an M25 rootstock will take up in 10 years time when putting a two foot tall sapling into the ground! Also bear in mind their long term needs for moisture, soil fertility and light. It can be tempting to try and fit in too many trees, particularly when there seems to be so much empty ground between them at this stage, but in the long run this will result in overcrowding and nutrient deficient trees competing for sunlight, water and space. In general aim to put larger trees at the north of the site and smaller ones towards the south and ensure that newly planted trees are well mulched for the first few years while they are becoming established.

Fitting In The Shrubs and Bushes

Smaller trees such as apples and pears on dwarfing rootstocks as well as shrubs and fruit bushes including black, white and red currants, gooseberries, Worcesterberries, etc. can be fitted into the spaces between the canopy trees. A planting plan for these can be created at the same time during the design process, or can be decided later on. Similarly you may wish to plant the shrub layer at the same time as the canopy specimens, or it might make more sense (and be more financially viable!) to wait a year or two. Be sure to incorporate some nitrogen fixing shrubs such as elaeagnus, sea buckthorn or Siberian pea tree into the shrub layer in order to help build and maintain soil fertility, and to encourage the presence of mycorrhizal fungi by adding inoculant spawn (these can be obtained in powder form) to any planting holes.

Designing the Ground Layer

Once the placement of the main canopy trees and shrubs has been decided, it is time to start thinking about the design of the under-storey. In addition to providing leafy salad and vegetable crops such as Turkish rocket, sweet cicely, lovage and perennial onions, one of the main functions of the lower levels of the forest garden is to create a living mulch with spreading plants such as wild garlic, Nepalese raspberry and wild strawberries. These keep the ground covered for as much of the year as possible, and prevent less desirable invasive species such as bramble, nettles and grasses from taking over. They also maintain soil moisture and prevent compaction through exposure to drying sunlight, heavy rain, etc. Nitrogen fixers like clovers, trefoil and vetches and deep-rooted herbaceous plants such as comfrey and sorrel accumulate minerals and nutrients in their leaves that help to build fertility in the garden. Aromatic plants such as feverfew, lemon balm, mint and tansy are said to promote health in the garden due to the anti-fungal properties of the essential oils they exude during the growing season. The design of the ground cover and herbaceous layers of your forest will determine whether it is going to be a high or low maintenance endeavour, depending on its complexity. Therefore I would suggest that if you don’t have a lot of time it’s probably not a good idea to plant more than a few species during initial establishment phase, instead adding more as the system evolves in later years.

To Bee or Not to Bee?

An eighth possible ‘layer’ to consider in the forest garden system is the animal component. Many insects, birds, amphibians and mammals will of course arrive in this thriving ecosystem of their own accord. If you have the opportunity you may also want to consider bringing in bees to improve pollination rates. As well as performing a number of useful functions within the forest garden ecology, you will also be providing these currently threatened species with a source of food and a relatively safe habitat – at present bees are disappearing due to the use of neonicotinoid pesticides and other industrialised agricultural practices. Contrary to commercial honey production, natural beekeeping is about working with, rather than suppressing and manipulating, the bees intrinsic behaviours – ‘giving to the bees’ as opposed to ‘taking from the bees’. The Natural Beekeeping Trust encourages ‘bee guardianship’ – keeping bees for the bees’ sake rather than for their honey – with an apicentric approach guided by the wisdom of the bees themselves. To me this fits well with both veganic and permacultural principles.

Maintenance and Access

Access for maintenance and harvesting of produce is important, so do not forget to design in paths that are wide enough to comfortably accommodate both yourself as well as wheelbarrows and any other equipment you may need to get in and out. There is a myth that forest gardening is a ‘no work’ system. I’m afraid this isn’t really true, although it is certainly less, and maybe even more enjoyable, work than much of what conventional food production entails. Certainly a forest garden is tolerant of periods of neglect that would be disastrous in an annual vegetable garden. Once established, the chief tasks on the forest gardener’s maintenance schedule are harvesting produce, some annual pruning, plus what Robert Hart preferred to describe as a little occasional ‘editing’ of any vigorous plants that are getting out of hand.

This is an extract from Graham Burnett’s The Vegan Book of Permaculture. Graham has helped to create a number of forest gardens, and maintains his own forest garden on an allotment near his home in Essex. He also runs regular forest gardening courses. Check out his new Forest Gardening Beginner’s guide here.